In the Realm of Yongwang (Dragon King) – Paintings by Dongkuk Ahn

Essay on Don Ahn: Dragon & Ocean – Recent Paintings, March 21 – April 3, 2007

Jeffery Wechsler, Senior Curator at Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University

This group of paintings by Dongkuk (Don) Ahn in the current exhibition makes for exciting viewing. Nearly all of the paintings exemplify a method of rapidly applied brushstrokes that hurtle across the surface with extreme speed and spontaneity. This is a technique that Ahn has employed at frequent intervals during nearly half a century of distinguished creativity. Throughout these productive years, Ahn has followed a path of knowledgeable interpenetration of Eastern and Western aesthetics, merging contemporary concepts and practices of abstraction with techniques and subjects drawn from his Korean heritage. In particular, Ahn’s art presents a meeting of the liveliest manners of Eastern brush painting-in particular, Zen painting and the so called “action painting” of American Abstract Expressionism. Although Ahn works in more traditional genres including quite realistic if stylized renderings of nature, especially trees, his continuing return to the more abstract and free-form modes is an ongoing source of inspiration for the artist, yielding an impressive, coherent, body of work.

Most of the works under consideration here derive from two visually and technically related groups. The earlier set, dating from around 1998, features relatively wide black brushstrokes of enormous energy rampant over citron or golden-yellow backgrounds. The dashing black elements, applied in a vigorous manner comparable to the traditional ink technique of “flying white,” enhance the sensation of breakneck swooping motion through the internal raggedness of each gesture, apparently shredded by its very force of its application. It is remarkable that this technique, originally used with liquid ink, maintains its fluidity in the medium of acrylic, which, though also water-based, is a much more viscous, heavy material. Nevertheless, Ahn’s brush marking in this medium art is the essence of lightness, dazzling in their aerial acrobatics.

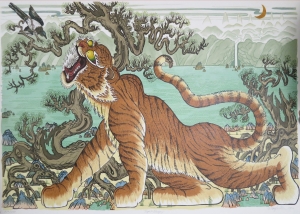

Ahn’s art has deep roots in the appreciation of nature and his cultural acceptance of the natural world as the ultimate source of all art. Ahn’s Korean heritage leads him to uphold this central aesthetic notion. These highly gestural paintings are conceived by Ahn as suggestive of a favored creature from Eastern culture-the dragon. Unlike in the west where the dragon is usually portrayed as a force of evil, it holds a place of honor in the folklore of the East, the dragon is a positive entity-spectacular and powerful, certainly, but also an auspicious creature, a bringer of good, Ahn showed especially keen judgment in applying this magical mythic representative of the “natural,” organic world to this series of paintings. Whether the titles came before or after the works were created is of no matter. The dragon is a wonderfully appropriate image for the joyously airborne antics of Ahn’s forceful strokes. Compared to their Western counterparts, Eastern dragons are much more elongated, snakelike beings, and the serpentine, coiling qualities of these beasts are find delightful abstract analogs in the multiple, abrupt twisting and turning of Ahn’s brushstrokes as they flap and glide through pictorial space. Eastern dragons also display a profusion of complex scale formations, tendrils and other extensions, which sprout from their bodies. These were apt vehicles for decorative linear elaborations for traditional artists, who reveled in such details for decorative effects; perhaps they are suggested as well by the many spurts, drips, and trails of paint that pepper the edges of the main forms in Ahn’s paintings. Even the fire-breathing abilities of dragons may receive their due here in the spatters and jets of yellow and red, such as those that erupt from Dragon 5.

The dragon in Korean mythology are viewed as beings related to water and agriculture, and often show their benevolence by ushering in clouds and producing rain. In the context, many Korean dragons were fancied to make their homes in oceans, river, and lakes. Indeed, one important dragon in Korean mythology, named Yongwang, is the dragon king of the sea. If the spirit of Yongwang inhabited Ahn’s art, for a while soaring majestically against the golden sky, it may have determined to return to its watery kingdom in the sea for a few years, only to reappear in Ahn’s art in order to invite viewers to experience the visual wonders of its undersea abode. In 2006, through a series of acrylic works on canvas with a predominantly deep blue background, we enter an evocation of the ocean deeps, where languid forms drift by, capturing our gaze with phosphorescent gleams of green, pink, and yellow. It may be that Yongwang makes one last appearance, slashing into the depths in Yellow Dragon, and then departs, leaving us to ponder the lovely marbles of this aquatic realm. In these paintings, Ahn’s gestural impulses are present but somewhat restrained, providing occasional active foils to a slower world of gently floating forms. Ribbons and rills of color are drawn into more intricate patterns here, and the overlapping compositional motifs develop more palpable spatial dimensions. Delightful color combinations, sparkling, yet refined, are dispersed with great compositional care, creating an overall sense of buoyancy and suspension. Appropriately, the titles are often unabashedly lyrical: Phantasy in the Deep Sea, Wave in Twilight-even Nostalgia.

In these paintings, one realizes the strange but compelling logic of alluding to the natural world through abstract mean. Many life forms of the sea tend to be more visually insubstantial, irregular, or ethereal than those of the land. Especially in the smaller forms, from plankton to anemones to seaweed, their shapes seem simple or amorphous. Ahn capitalizes on this situation, using the semi-random markings of his active gestures to bring forth intimations of life beneath his brush. The degree of abstraction or realism lies in the perception of the individual observer. Likely by pure serendipity, a rapid gesture or two realized the Black Fish that popped into vies at the center of that painting. Elsewhere, in Coral and Red Fish, the “fish” are no more than brief squiggles, and the coral is a glimmering but ghostly affair of simple textured strokes. Finally, general allusion trumps specific identification, and a fragile crisscrossing of strokes of varying widths offers a conceptual vision of Loving movement in the Ocean.

Together, the paintings in this exhibition demonstrate the steady evolution of Ahn’s hybrid world of abstraction and nature. He continues to transform venerable techniques themes into fresh worlds of visual pleasure and insight.

The Korean Society—The Meaning of Dragons in Korean Folklore

To Mark the opening of an exhibition of Korean dragon paintings, author and Folklore specialist Heinz Insu Fenkl, director of the Interstitial Studies Institute at SUNY New Paltz, lectured on dragon symbolism in both the East and West. Due to its association with serpents in the Old Testament, he explained, the dragon was viewed as auspicious and usually was depicted as a magical creature if unsurpassed power and vitality. Fenkl went on to elucidate the subtle but important differences between Korean dragon iconography and the more widely known Chinese dragon imagery. Dragon mythology originated in ancient China, Fenkl noted. The legendary founder of Chinese civilization, Fu Hsi, was said to be half-man, half-dragon. After the folklore disseminated to the Korean Peninsula, however, local artists and storytellers made their own adaptations. Compared with their Chinese counterparts, Korean storytellers placed more emphasis on the spiritual powers of dragons. In fact, dragons play a role in many of the most important Korean myths and fables even though they generally are assigned to peripheral roles where their actions reflect the virtues of the main characters. Fenkl described one important figure, the Dragon King, who was said to live in a palace beneath the sea and was generous and welcoming to a fault. Dragons are still omnipresent in modern day Korea: on billboards and logos and in brand names and commercials.

Unfortunately, while Koreans recognize them, these days knowledge of the folklore behind these cultural icons is fading. “This is all the more reason”, Fenkl concluded, “to take the time to really study the paintings hanging in the gallery.”