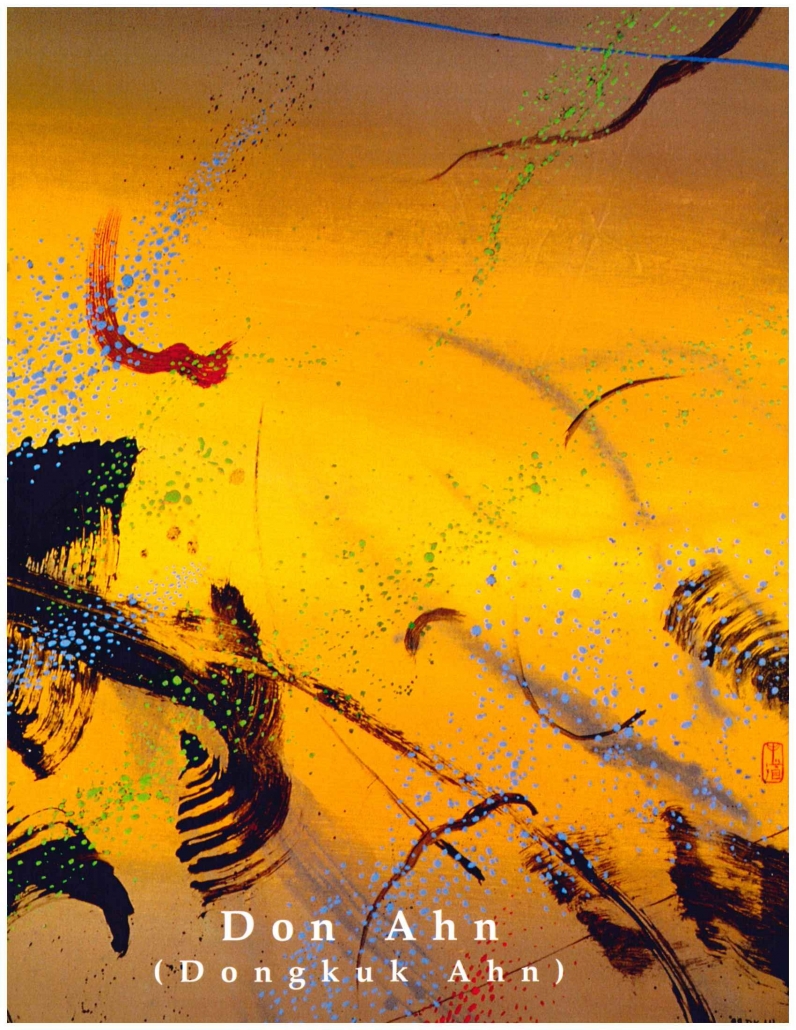

Don Ahn’s painting: Record of Nostalgia and Incomplete Dreams

Essay on Don Ahn (Dongkuk Ahn): Record of Nostalgia – Recent Paintings, September 28 – October 26, 2000

Gordon Rhee, Professor & Art Critic CUNY

Each of us has a past and memories associated with the experiences of that past. Remembrance of bygone days-verdant hills and winding trails, fleecy clouds and singing streams, the trace of certain words reminiscent of childhood, incidental retrieval of facts from oblivion, situations deduced from casual observation – the nostalgia sometimes serves as psychological palliative to fill the deficiency or void of our emotions or can provide a handy escape from our realities. Complete revival of one’s memory of the past may be impossible to achieve. Because of this uncertainty of memory, our travel into that world of vagueness can be a process of self-affirmation that takes place in the secret space of privacy and self-contentment (this can lead to a sort of narcissistic mix of melancholy and delight).

Don Ahn is a pilgrim in search of the fragments of such memories. His work is an incomplete record of the dreams implanted in his brain. Ranging from archaeological interests through the inviolable internal world most private and most secret, his travel into his past proceeds with curiosity and fervor becoming of an explorer who sails for the most intimate yet strange land. On the expansive land of the canvas (my imagination sees him bent on works that almost look like all over painting), he uses a minimal amount of contours, which enables him to deduce a certain image, and thins with a single compass in his possession.

The compositions he sets up either exploit the psychological effect of colors, or an arrangement of his own desires – wishing to trace back the stream of time, but failing to produce any information to fulfill his pleasant wandering. To record the trace of his trails of the past on a blank white sheet, relying only on his own memory, could be a futile waste of his labors for a vague and preposterous goal. Nevertheless, his work may be a process to affirm the non-redeemability of his own dreams through this perfect attrition of his energy.

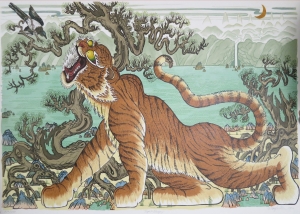

This territory of desires and the space of nostalgia and longing is as much about how the memory in the process of oblivion seems to augment the sense of bewilderment we must endure in the depths of that purple area. Beneath the surface which he finished with uniform brushwork on the two big canvases, the trace of the past he pursued and signs of his urgently felt desires are bared, revealing the evidence of his final resistance, as if refusing to have his memory completely erased. The only visible image to be discerned in this work is of a swine, depicted as if swept over and carried away in a flood. Even if he had covered the base drawing with very forceful brushwork this could not be called a return to or restoration of the plane. Beneath the surface that looks like a converging vortex, a few signs looking like codes are hidden, as if keys to the hidden meanings of the concealed base drawing.

Hereupon, we may note that his journey into his past is not confined to the chronological dimension, but leads into his own internal consciousness as he stands in front of his work. Therefore, this journey is in preparation for a new start, or the start of work to dismantle what has already been constructed.

This dismantling is a disassembly of his uncertain memory, and a disjunction of the fixed frame of methodology and ideas. Thus he dreams of being free from norms or institutions, or from any fixed rules and mores. For instance, he sought a sense of freedom using an irregularly shaped canvas, but soon found that it rather restricted his freedom, so he came back again to the use of a regular canvas. In other words, he does not hesitate to discard what he once believed to be freedom, once it proves to be fictitious. To start in search of a new land, declining to ensconce himself in an old one, is a challenge he can put up as an artist, as a game, or as a pilgrimage. On the other hand it may denote a willingness to acquiesce to the uncertainty of painting.

What then does this revolt against to the norms of painting promise? The problem faced by contemporary art may be that we cannot affirmatively proclaim its positive aspects at first sight.

At this time, when art refuses to be a meaningful account or narration, and is sinking deeply into the internal context of art itself, painting must proclaim that painting itself proves the absence of truth. To merely restore painting into a formal context, and to dismantle the multitiered structure of meaning in painting for the purpose of that restoration must be a product of defeatism, surrendering the communicative power of art. This may lead to tolerating the incessant, repetitious dismantling. There is then the risk that this dismantling done by Don Ahn may result in sacrificing the object – the world or the painting itself – for attainment of perfect freedom he is alluding to. This can be compared to living in a closed space, or vacuum, while attempting to realize naïve dreams (realization of perfect freedom) that are impossible to attain. This may end up as a self-contented addiction to an ideological sense of freedom within an abstract, transcendental world. Therefore, painterly freedom must have as its prerequisite a mutual relationship of communication.