Don Ahn’s Zen Paintings: The Substance of Speed, The Fullness of the Void

Essay on Zen & Void: Don Ahn (Dongkuk Ahn) – Paintings, Ink on Rice Paper, January 31 – February 26, 2004

Jeffrey Wechsler, Senior Curator at Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University

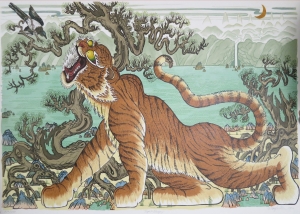

At first glance, the current exhibition of ink paintings by Don Ahn may appear to represent a particular stage, or even a concentrated moment, within an artist’s career. Together, the works form a coherent visual ensemble: sweeping gestures of black and watery gray dance across expanses of white rice paper. In each, there is a relatively spare number of major brushstrokes; most are enlivened by trails of spatters or drips. One could easily imagine the artist moving from one surface to another, quickly filling a waiting array of sheets, working out a sudden inspiration within a given temporary theme. It is therefore important and intriguing to realize that the paintings gathered here were made at various times spanning over four decades. Black-and-white paintings such as these have not been Ahn’s only theme; he has created more realistic work, including images of landscapes and trees, as well as abstractions in dense, bright colors. These several themes are revisited, sometimes in modified guises, in a manner that suggests both the cyclical forces of nature perceived through Zen and other Eastern philosophies, and also the artist’s perception of past experience – tradition- in personal and wider cultural senses.

Among the central characteristics of East Asian civilization is its deep and abiding respect for tradition. This notion runs through the region’s culture, philosophy and art. One learns from the past, acknowledge and respecting the vast range of achievements it offers as touchstones for education and emulation. Indeed, even the copying of masterworks can be deemed a creative act, if the process shows that lessons have been learned. Thus, returning to past themes – even in one’s own work – does not show lack of imagination, but a willingness to expand upon past knowledge, honoring previous accomplishments by adding new links to a chain of artistic continuity.

Ahn’s abstractions reveal a connection to the venerable tradition of painting by Zen monks. For many centuries, one expression of Zen philosophy has occurred through art of extreme simplicity of form and rapid yet elegant rendering. Recognizable images represent the bulk of this art, to be sure, but the mode has at times produced works that come close to abstraction in spirit and visual incident (and especially so when applied to the art of calligraphy). This is a major lineage for Ahn’s ink paintings.

Despite the generally abstract aspect of these paintings, another Eastern tradition plays a key role in their making – the brief in the centrality of nature to all human enterprise, including art. Since the essential purpose of traditional Eastern art is not the mechanical replication of the external aspect of things, but the attempt to capture and transmit the vital, living quality of all aspects of nature (the ch’i), the underlying intention of this art is fundamentally philosophical or abstract. It is quite commonplace for an artist to begin a landscape painting by marking the blank paper with rapid, spontaneous dashes, blots, and puddles of watery ink. These marks may be virtually abstract, appearing unrelated to nature. Yet they act as a visual and conceptual framework upon which the artist will build a representation of natural forms, whose forms ultimately benefit in freshness and vivacity from the freedom of the initial strokes.

The active, splashing quality of Ahn’s methods can prove particularly valid to evoking nature’s essences. For example, the swirling spatters and single broad stroke of one of Ahn’s works suddenly resolves from chaotic abstraction into perceptive symbolism when its title is given: Broken branch in the Rain. How better to represent the evanescent phenomenon of rain than through the visual remnants of actual liquid flung in droplets against a surface? The physical process that created the broken branch is vigorously depicted in the spiraling trails and allusions to a windswept atmosphere, even while the branch’s isolation within the tumult elicits a sense of the fragility of life with a special poignancy. The titles of other paintings offer associations with a tree, the wind, or the ocean. Broken Branch in the Rain can also act as a potent introduction to two apparent pictorial opposites that – as befits work inspired by Zen – serve as dual sources for these paintings’ visual and conceptual effects. Each painting creates a careful balance between two elements: a few relatively dense black strokes, and expanses of relatively uninflected or nearly empty space. The black marks are active and intense. Flailing about the surfaces, leaving contrails of black and gray, the strokes evince a madly hurtling brush attack against the paper. Every mark seems to have been applied at extreme speed. Nevertheless, one remarkable aspect of these strokes is how completely even the most explosive of them ultimately resolve within the paintings as compositional pivots and focal points of visual weight (but without reducing their sense of unbound energy, yet another Zen-like paradox). The two-stroke formation that writhes at the center of Struggle of Yin & Yang has ink drops erupting from its tips, and its irregular sides are ragged, like a banner torn asunder by fierce winds. Yet the shape is fully there, strong and supple and giving enormous visual impact to the work. The great looping gesture that dominates Zen Circle II bespeaks a brush snapped across the paper at a breakneck pace. However, despite its implications of continuation beyond the left and right edges, it still gathers itself up into a formidable, tense, and tactile entity, anchoring the picture. Somehow, speed becomes the medium for suggesting presence and substance.

In many of these paintings, the strokes are accompanied by spatters that arc into the surrounding areas, creating a transition from the density of the marks into the whiteness of the paper. This untouched space usually accounts for a vastly greater proportion of each painting than the inked areas. To Ahn’s Zen way of thinking, though, this is not empty space, nor does it reflect the Western concept of “negative space.” Instead, this is the Void, a palpable presence that fills the cosmos, and by implication, the open areas of a painting. “Empty” space is simply not so within Eastern philosophical traditions: it is filled with Tao (the fullness of existence), and ch`i (the energy within it). In a straightforward acknowledgement of the fundamental place these concepts hold in his art, Ahn has titled this exhibition “Zen and Void.” With these words, a viewer receives sufficient direction from the artist regarding the sources of his work, and is then free to enjoy the sheer visual pleasure of these exciting yet profound images.